Oh, birthdays,” Sir Ian McKellen growls, on the occasion of his 82nd. “At my age I don’t do birthdays.” The wider world has not yet been informed, however, and cheerful cards have come in stacks to McKellen’s London townhouse. Messages chime in on his computer and two landline phones ring on his desk, one after the other. “But, darling,” McKellen says, answering a call and interrupting a well-wisher mid flow, “I’m trying to avoid it all this year.” Guilt, he explains to me, later. He leads us through to a sitting room. “Actors don’t need this special attention, I’ve realised. We get cards and presents on first nights. Everyone makes a fuss of us. Birthdays are wonderful things for people who don’t get treated as special all year round.”

McKellen throws himself down in a winged armchair and croaks out an epic smoker’s laugh, one of those laughs that begins in silence (mimed really) and soon becomes an extended hum in the back of the throat, then a wheezy bark. Devoted to his cigs, he will step out on to his riverside balcony whenever he needs one, staring out over the Thames while he puffs, pulling on a tweedy overcoat if it’s cold. Between times he sucks on Polo mints. One goes into McKellen’s cheek, now. The rest of the packet he leaves perched on his tummy in reach. “Where were we?” he asks. “Birthdays?”

I’m wondering, I tell him, whether we ought to surprise actors once a year by telephoning them to say they’re not so special after all. McKellen snorts. “That’s it, the reversal. I like that.” And he waits – as if expecting me to list the ways he’s run-of-the-mill as a performer. Of course, I can’t do it. This is Sir Ian McKellen, perhaps the best we’ve got, that ideal embodiment of Tolkien’s Gandalf across six Hollywood movies, a landmark Richard III on stage and screen, my favourite Magneto, a critically acclaimed Macbeth, Sherlock, Edward II, Rasputin besides. Later this year he will play Hamlet, for the second time in his career, in an age-blind production at the Theatre Royal Windsor. McKellen only has to growl out some lines from the play for the hairs on the back of my neck to quiver.

“To die, to sleep. To sleep, maybe to dream… You know, it was not my idea to play Hamlet again. I was invited to, by Sean [Mathias, McKellen’s longtime collaborator], who more than most directors I absolutely trust.” McKellen says that he and Mathias were in agreement. There had to be some point to it all, if McKellen was going to return to a part that he last played 50 years ago. By the sound of it, the new production will have fun with the crisscrossing age dynamics, as a young-ish character inhabits an older man’s body; as an experienced pro brings all his technical nous to bear on a role that’s traditionally played by an actor nearer the start of a career than the end.

“When I was young I was always playing old parts,” McKellen says. “And, of course, I was having to imagine it. Because what does ‘old’ mean? I had no idea! Now that I’m old I do know. And I also know what it’s like to be young. Because as you get older, inside, you’re ageless. Inside? Quite honestly? I feel about 12.”

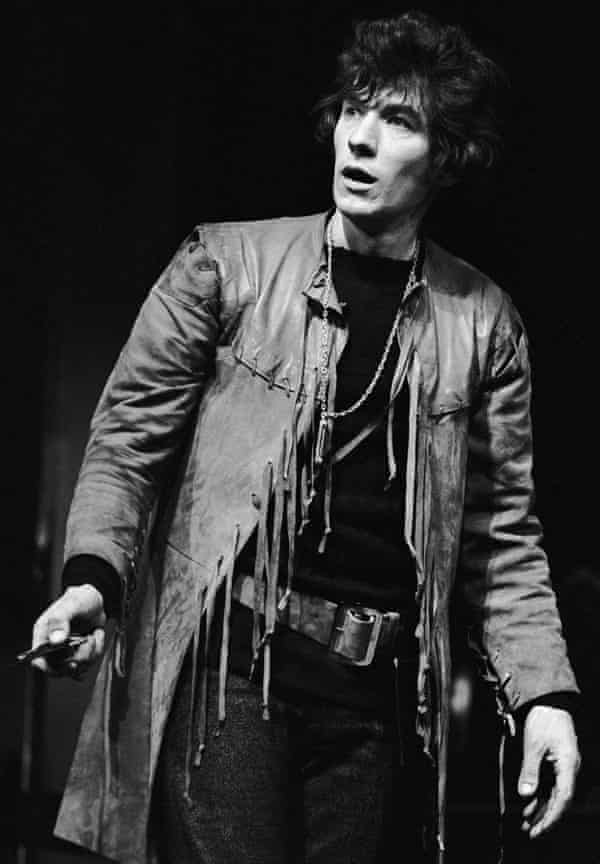

A word, here, about his face. Fixed to look craggier when he played Gandalf two decades ago, it has since caught up with some of those ageing effects achieved by the Lord of the Rings cosmetics team. In a funny way this has made him appear more youthful, though. When you look at the pictures of McKellen turning 50, for instance, cutting his cake backstage at the National with a prop sword, he was skinnier, moustached, rather terrifying. Now the laughter lines are more pronounced around his eyes, creating the pleasant impression that he’s always fresh off a giggle. His grey hair, tufty and short, skews off at a million angles in a way that fashionable young men will strive after. He says that, in rehearsals for Hamlet, cast mates of all ages have said they keep forgetting whether he’s 80-odd or 30-odd. “I’ve been having the time of my life.”

Why is it that actors can go on and on into their 80s and even 90s, I ask him, when artists in other disciplines tend to fade away earlier? “It’s the nature of the job that allows us to carry on, I think, rather than the nature of the people we are. Don’t forget, actors are only the conduit, not the source. So we’re not – as a writer would be, as a composer, as a painter – having to reimagine the world around us or within us. We are presented with the material. And then we just have to bring it to life. Some actors retire, but usually because they can’t learn the lines any more. That hasn’t been the case for me. Fortunately. At the moment.”

He leans forward and gives the wooden table in front of him two sharp raps with his knuckle. Next door, the phone rings again, as friends and acquaintances seek to remind him that another year has passed.

When McKellen was a little boy, he fell in love with a summer-holiday friend called Wendy. They wrote each other letters for a time. They were about 10. And that was it, the last heterosexual relationship of his life. By the time McKellen was a teenager he knew he was gay. His mother died of breast cancer around then and he never had a chance to speak to her about it. Perhaps in Greater Manchester in the 1950s (McKellen was raised in Burnley, Wigan, Bolton) there wasn’t much that could be said. He never told his father either. The fact that both his beloved parents died without knowing this one essential fact about him remains a great regret.

Having to hide his sexuality, however, turned out to be a total boon for the career. Being gay in those days necessitated a talent for disguise. And McKellen found in acting a profession that rewarded this talent. He appeared in plays as an undergraduate at Cambridge – correctly sensing, he once said, that this was where he would get to meet the colleges’ other queers – and later as a graduate he got a job in regional theatre in Coventry.

I ask whether he was somebody who fell in love often when he was young, and in answering McKellen sings a snatch of song from a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical. “You know that lyric, in South Pacific? ‘You may see a stranger across a crowded room, and somehow you know, you’ll know even then, that somewhere you’ll see them again and again.’ Well I recognise that feeling. But no, I don’t think I was forever falling in love. Early on in life, I lived with people in a – well, what would now be called a marriage, I suppose. Monogamously. And that suited me very well. So I wasn’t always on the lookout. I didn’t need to be.”

As more text messages ping in the next-door room, he reminisces about the advantages of a romance conducted entirely by handwritten letter. “I say to younger people, you may have instant communication on your phones, and that’s terrific. But the wonderful, thrilling pain of waiting to see if a beloved will reply to your last letter! I can’t imagine not knowing that feeling.”

Has he kept any of those old letters?

“I have,” McKellen says at length. “But they’re painful to read. I can’t bring myself to. It takes you back so immediately. You see the mistakes you made. And there are regrets. If it’s a happy letter from somebody you loved, and they’re dead, well, you have very mixed emotions.” We talk a little about the risks of being gay in the 1960s and 70s. He knew people who were arrested, “simply for having sex”; but McKellen admits that for large chunks of his youth he more or less ignored the discriminatory laws at play in Britain. As a closeted gay man in stable relationships, he felt he could afford to. “I didn’t feel particularly disadvantaged by the very harsh laws that prevailed up till then. The laws were absolutely cruel, but I didn’t take them personally. And I only began to think about it, and realise what the situation was, when the Thatcher government decided to introduce the first bit of anti-gay legislation for nigh-on 100 years. That I took personally.” To make a political point, he came out. He was in his late 40s and well established by now as an actor on stage and screen.

That first job in Coventry rep had led to employment in London with the RSC. He did a season of Shakespeare there, then in Stratford. A nice mention in a national newspaper review got him an agent and got him going. By the time McKellen was 30 he’d been Richard II in a hit production that toured out of the Edinburgh festival and was shown on TV. The drama critic Harold Hobson described McKellen as an actor with “the ineffable presence of God Himself”. Riding off that success, he tried being Hamlet in 1971. “We did it in Edinburgh, we did it in London, we did it in Europe, we did it on television. I was very happy. Bu-u-u-ut, I was not very good in the part.” Hobson, once so flattering, wrote that the best thing about McKellen’s 1971 Hamlet was the curtain call.

I ask whether that experience has left him wanting a do-over.

“A what-er?”

Another crack at the part.

“Oh, that’s what I’m doing now, is it? A do-over?” McKellen ho-ho-hos.

Anyway it’s not clear he would have had time to try Hamlet again before now. Because McKellen has been employed in the theatre so consistently, so reviewably, night after night after night, it’s weirdly easy to find out exactly what he was up to on any given historical occasion. Summer of the moon landing: The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie in Liverpool. The night that Thatcher was ousted: Richard III in Paris. By my count, he has played seven of Shakespeare’s kings on stage, also Romeo, Iago, Claudio, Coriolanus, Faustus, Napoleon, Inspector Hound, Captain Hook and Widow Twankey.

As for his screen career, though prevailing Hollywood wisdom suggests that if you come out of the closet, the job offers climb into the vacated space and vanish, McKellen actually found he thrived as an openly gay actor. He was the arch villain Magneto in the first of several X-Men movies in 2000. Between 2001 and 2014 he was the arch goodie Gandalf in six of Peter Jackson’s Tolkien adaptations. After decades of being buttoned up about his private life, he started to write an honest personal blog from the set of Lord of the Rings in New Zealand in the early 2000s. He has since maintained the habit of public diarising, sometimes publishing snatches of memoir on McKellen.com, his website.

Recently, he tells me, he came close to agreeing a contract “for a very handsome sum” to write a proper autobiography. In the end, the long book tour that was stipulated in the contract put him off and McKellen abandoned the project. But before he stopped writing he would often wonder, he says, who exactly his readers might be. He has amassed a fairly unique fanbase, made up of Shakespeare regulars, Tolkien nuts, comic-book readers, and Harry Potter obsessives who continually mistake him for Michael Gambon, the actor who was cast in the Warner Brothers movies as the wizard Dumbledore.

“I guessed there would be people reading any book of mine to discover more about Gandalf,” McKellen says, “but would they know much about Shakespeare? And vice versa. I kept wondering, who am I writing this for?” He ended up asking advice from a close friend, the novelist Edna O’Brien. She suggested he write it for his mother. He should tell her what he’d been up to since she died. McKellen sighs. “Well. That’s sweet, isn’t it?”

The memoirs have been shelved. But I ask him, what would he tell his mother now, if he had the chance?

“My aunt once told me that my mother thought it would be a wonderful thing if I went on to become a professional actor. Because actors gave so much pleasure to her in her life. So I’d want to tell her that, about my work. I’d want to tell her: thank you. And I’d want to talk to her about the people I’ve loved over the years. I’d want to tell her all about it and hope she wouldn’t… That she wouldn’t find it… That she wouldn’t be upset.”

Earlier, when McKellen was talking about his first Hamlet production in the 1970s, he praised castmates before realising, with a grimace, that every single one of the actors he mentioned was dead. All day, the lines he’s instinctively recited from Hamlet have been about death, dying, some mysterious next chapter, “the undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveller returns”, as he growls. Actually, McKellen says, he doesn’t expect much in the way of an afterlife, when he goes.

“I think I decided a long time ago that this was it. Life is not a preparation for the hereafter. Maybe I’m in for a delightful shock. A surprise. No. Death is death. So, then, what have I spent my life doing? If this is the only life I’ve got? Well, I think I found something I was good at doing. I feel that that’s been my contribution… What will it be like, I wonder? Will it be preceded by a rage against the light? Will it be painful? Because it’s certainly coming.” Half-speaking, half-whispering now, McKellen recites one more line from Hamlet: “If it be not now, yet it will come – the readiness is all.”

“And do you know,” he adds, “I think more people who die are readier for it than the rest of us left alive would guess.”

McKellen sits back, sprawled, in the armchair. He is youthful and elderly all at once, the junior actor who used to add on decades for theatre parts, the Hamlet who’ll soon try his best to ignore being half a century older than the source material dictates. Before I leave him to the remainder of his birthday, he unravels a mint from his packet and looks out of the window, singing a few lines from another old musical, Showboat. “Tired of living,” McKellen croons, softly. “Scared of dying. But old man river? He just keeps rolling along.”

Hamlet opens on 21 June at Theatre Royal Windsor; and The Cherry Orchard opens on 10 September (theatreroyal windsor.co.uk)

Stylist Helen Seamons; photographer’s assistant Matt Walsh; lighting by Michael Furlonger; stylist’s assistant Peter Bevan and Alice Dunlip; grooming by Juliana Sergot using Lancome and Kiehl’s

from Lifestyle | The Guardian https://ift.tt/35iHjzA

via IFTTT

comment 0 Comment

more_vert