The biscuit was only barely covered. If I’d had to guess, I’d have said 30% of its surface had chocolate applied, and that’s being charitable. Certainly more charitable than the manufacturer of the Jaffa Cake in question, who I pictured as God’s perfect miser; a Scrooge-like figure toiling in a candle-lit factory, peering over their bifocals to smear homeopathic levels of chocolate on one sorry corner of my favourite tea snack. I was 10 years old, and had never had a particularly strong sense of myself as a consumer champion, but this biscuit, this disgrace, roused something inside me.

“Dear McVitie’s,” I wrote, addressing the entire company in my missive. “I was shocked and appalled to discover this Jaffa Cake (enclosed) in such a state.” In hindsight, I was savvy enough to moderate my speech to sound adult, but not perhaps worldly enough to consider enclosing the foodstuff itself in plastic before popping it in with my letter. By the time I posted it the following day, I remember already noticing some of its soft greasiness had permeated the envelope, but I reckoned this was probably just the way things were done. Evidently it was, as two weeks later I received a letter apologising for my suboptimal experience, along with an invitation to tour a factory, and two whole boxes of Jaffa Cakes. These, I am happy to report, were perfectly chocolated.

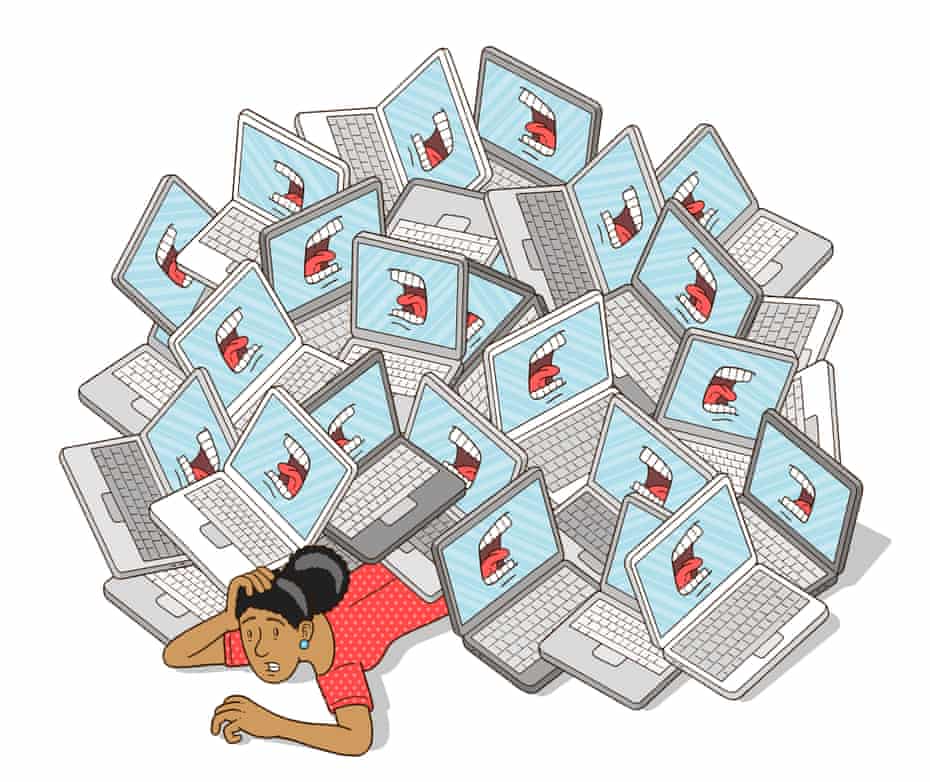

That victory won, I retired from professional complaining, preserving my 100% record in amber for all time. Others, however, have kept the faith. The 18th century’s finest polymath, Samuel Johnson, once said: “Man alone is born crying, lives complaining and dies disappointed.” It would seem that the British public has taken this more as a recommendation than a rebuke. While canvassing people for this article, I received more than 150 replies in 24 hours and read, amazed, as a grateful public unloaded stories of consumer activism, tweet by tweet.

In 2019, the Mirror reported that 33% of UK residents polled had left a negative review online, and 70% of those had done so within the past year. Two weeks later, the Daily Mail lamented the findings of an entirely different study claiming Brits spend 10,000 minutes of their year complaining (a moral high ground it would have been easier to maintain had they not embedded that very article with links to their own columnists complaining about woke millennials). Perhaps “mentor7” summed up the mood of that room best in the comment he left under that article, saying: “It’s wonderful. There’s so much to moan about every day and it’s on the increase. I love moaning. It makes me so happy.”

This outlook may now be the rule rather than the exception. Ofcom’s recent report for the 2020-21 financial year revealed it had received more than 145,000 complaints about broadcasts, a 400% increase on last year’s figure of 34,545. (Additional to those numbers, the BBC received 110,000 complaints about the wall-to-wall coverage of Prince Philip’s death alone.) So what has caused this boom in belly-aching?

“The numbers can be explained by a few big-ticket items,” says Adam Baxter, director of broadcast standards at Ofcom. “Just before the end of that reporting period, this March, there was the issue around Piers Morgan and his comments about the Duchess of Sussex. That got north of 50,000 complaints by itself. Last September, we also had the Diversity dance troupe’s performance on Britain’s Got Talent [which included imagery and messaging in support of the Black Lives Matter movement] and we got over 24,000 complaints for that. Those two incidents alone accounted for more than half the complaints. But, even if you discounted those, you’re still looking at 70,000+ complaints, which is a huge increase in and of itself.”

Baxter is open-hearted and expressive in conversation, very much the kind of person to whom you’d be delighted to complain about a faulty Jaffa Cake. At one point during our video interview, the connection stalls. Cursed by comedic genius, I ask if I can make a complaint about my broadband service through him. He politely tells me that would fall under telecoms not broadcast, but in a tone that suggests he’d probably pass me to the right person if I wanted. He certainly doesn’t see the recent rise in complaints and complainers as signs of a nationwide tendency for tedious begrudgery, and rather views it as a natural expression of public interest.

“I really love my job,” he says, “when people find out I work for Ofcom, they will always have opinions about what they’ve seen and watched on telly or heard on radio – often very strong opinions. If they know something has had loads of complaints they’ll always ask me what I think. Of course, I have to be careful and very politely say, ‘Oh, how interesting,’ without saying whether I think it’s right or wrong.”

The breadth of Ofcom’s remit is fairly staggering. Baxter oversees a team of 40, within Ofcom’s 1,000-strong staff, charged with the thankless task of assessing every complaint that comes in related to breaches of the broadcast code. In practice, this is exactly as large a job as it sounds, involving a mammoth amount of data capture and analysis.

“We have a wonderful bit of software that grabs all the most prominent channels for complaints. So, if we get a complaint, we can go to that bit of the software and pull the recording. If we don’t record a channel in-house, we will write to the broadcaster and they have five working days to come back to us with a recording.” This extends to the process of assessing non-English-language programming with dedicated staff trained for precisely this purpose. “We have in-house translators for some of the languages that have recurring complaints about incitement to religious hatred and hate speech. I have a team fluent in Urdu, Punjabi, Pashtu and Arabic, and they’ll often be doing the recording”.

For a view from the ground floor, I spoke with former complaints desk operator, “Paul”, who spent years working on the phones, answering queries that came in from members of the public across all of Ofcom’s remit.

“When I was there,” he says, “the type of people who complained about broadband or their phone company would be ordinary people who’ve had a bad experience, who were complaining because something was costing them money or was a major inconvenience. But when I was getting calls through the broadcast queue” – he pauses – “I was almost expecting them to be a little eccentric. I already had my guard up.”

He recalls one example, from more than a decade ago, like it was yesterday. “I remember speaking to some guy for 20 minutes because he was upset about a repeat of Trisha that featured a phone-in. Because it was a repeat, text on the screen said: ‘Lines are now closed – this is a repeat.’ This guy was incensed. I said: ‘You didn’t call in, did you?” And he said, ‘No, but it’s not very nice is it?’ I told him their only other choice would be not to run repeats…”

Paul’s attempts at conciliation fell on deaf ears. Then he realised his caller was not upset by false advertising, but that it contradicted his favourite TV presenter. “They’re making Trisha out to be a right mug: she’s saying phone in and as she’s doing that, on the screen it says, ‘Don’t bother.’ They’re making her look stupid.”

Paul had previously worked at the Advertising Standards Authority, which gave him a further insight into the machinations of the Great British Complainer. “When I was there,” he recalls, “the most complained-about ad had nothing to do with racism, sexism, or misleading or fraudulent content” but a KFC ad that enraged viewers because it featured office workers singing with their mouths full of chicken salad. He pauses for emphasis. “It wasn’t just like that one crept over the line and beat the record, it completely smashed the record. People went apeshit over that ad.”

To some extent, the pull of complaining may be tied to this need to get something off one’s chest, or to strike back against corporate or media behemoths that seem untouchable to the lesser mortals who use their services. Software designer Barney Carroll intuits a deeper, sociological reasoning for our need to complain. “Jovially indignant stories about complaining to customer services until you got loads of cool stuff,” he says, “seemed to me an intrinsic component of my grandparents’ experience of the postwar social contract.”

Or maybe we’re all just children, pretending to be adults, in order to secure free chocolate. Musician Emma Langford was one of many people I spoke with who assured me my Jaffa Cake activism was in no way unique.

“As a kid I got a box of Milk Tray and the Turkish delights were solid chocolate,” she told me. “I wrote a distraught letter of complaint but – assuming I wouldn’t be taken seriously as a kid – I posed as an adult man who bought them for his wife”. Furnishing me with a photo of the letter, now tattered from its position as a well-worn family heirloom, it was clear her story checked out.

“To whom it may concern,” it begins, in the time-honoured manner of every child hoping to sound like an adult. “I am writing in complaint of one of your boxes of chocolates.” However, the letter’s fussy tone reaches its peak in the following paragraph. “On The 10th of February, I purchased a box of your confectionary selections, Cadbury’s Milk Tray, for Valentine’s Day as a romantic gesture towards my wife.”

If the mechanisms by which we complain have changed, the central urge may be the same as it’s always been, only now enabled by the instant gratification of social media and dedicated teams of people combing through our concerns about broadcasts, faulty biscuits and the horror of people singing with their mouths full. There is also the possibility that a year indoors has sharpened our sense of irritability, while keeping us free of the distractions that blighted the careers of previous generations of complainers, stifling their ability to complain as freely as we can now. Perhaps it’s not surprising that Covid coverage has itself been cited in 14,000 complaints to Ofcom in the past year.

“We’ve no detailed deep-dive on the reasons people complain,” concludes Baxter, who is resolutely thoughtful and empathetic when discussing complainers. “Clearly,” he says, “it’s a range of things. It captures the gamut of human emotions. There are people who are very agitated and angry, especially depending on the issue, and people who just want to vent rather than address that issue, per se. There is some anecdotal feedback of people writing back to us – not many, to be brutally frank – whose complaints haven’t been upheld, and saying: “I don’t agree with your decision, but thanks for taking the time to explain it to me.” Perhaps, then, his isn’t such a thankless task after all.

Follow Séamas on Twitter @shockproofbeats

from Lifestyle | The Guardian https://ift.tt/3vixyfw

via IFTTT

comment 0 Comment

more_vert