When the first lockdown began and Boris Johnson finally pointed his finger down our throats and warned us in a tweet that we must stay at home “as we work together to fight this virus and keep everyone safe”, he also spoke in a speech of the “fortitude of the elderly”. Suddenly, the rising stats of loneliness began to be bandied about on every news feed. One in four adults said they had experienced feelings of loneliness in the previous two weeks, according to a Mental Health Foundation survey, from last April. The number of people who felt “always or often” lonely reached 8%, the highest it’s ever been on record.

Before the word “bubble” was revamped to mean “people you could have actual physical contact with”, I lived what I now refer to as the “fast life”: always moving, constantly adrenalised, permanently stimulated. My alarm would scream down my ear at 6.30am. I’d squeeze my way into a spin class at 7am, then eat a bowl of Tupperwared oats on the train as I made my way to a café to start work for the day. I’d spend money I didn’t have on overpriced coffees and average lunches, and then I’d rush to audition for an acting part, making small talk with my doppelgängers in the waiting room.

And then boom: the pandemic. We sprinted to a pause. A kind of “slow life” began and I was left in a small, rented flat, with screens of different sizes to keep me company.

A few days into lockdown, a Facebook notification suggested I join the local Mutual Aid, a community group that helps and provides companionship to the most vulnerable. I thought, fantastic, a focus, and clicked through to the WhatsApp group, desperate for distraction. But the group seemed inactive; there were very few messages. Days and weeks passed in silence. And then, one morning, one of those brain-foggy beginnings that seemed then to characterise the pandemic, the group pinged to life. I’d spent the first few hours of the day watching my uncle’s funeral on Facebook Live – a victim of the coronavirus. But the message pulled me out of the stupor. “Old man seeks friend in Bethnal Green,” it read. It had been sent by Wilma, the head of the group. Without a moment’s thought, I replied: “Me! I’ll take him. Me!” And before long his number was shared, along with a brief “good luck”.

Alberto.

92.

Italian.

Wants Friend.

I sat bolt upright on my bed and called him straight away.

Alberto gives a short, sweet rundown of his life. Originally from Genoa, he maintains a gorgeously rich Italian accent. He is retired, but busy. He learns Mandarin by tape. He rereads interviews with his favourite golden age actors. He cooks. He listens to music, mostly classical, a lot of Verdi. He spends at least 10 minutes every day taking in sunlight from his bedroom window, before completing a self-designed workout, which, from what I understand, is a mix of tai chi, yoga and squats. He tells me this during our first call, prior to which I was anxious, and which, in his quiet, discreet way, Alberto managed kindly and competently. Before I realise it, we have spent 40 minutes talking.

I told him I’d call him again in a few days’ time. He told me not to put pressure on myself. “Life is difficult,” he said. If I didn’t feel up to the task, he would understand. Well, fine. But I found I couldn’t wait. Alberto’s rootedness, his comfortable slowness, his calm – it was contagious. Within a week, it was agreed: I would call him every other day at 6.15pm, and we’d chat. He would describe growing up in the Italian hills. I’d ask him why he moved to Bethnal Green. He’d ask about my work, then tell me about his favourite movies. The movie chat would turn to book chat, which would turn, more broadly, to “creativity”. I encouraged him to start writing a diary; he encouraged me to rip up my to-do list. Our conversations were rich and we laughed. There was, I felt, connection.

From the first call, there was something about our exchanges that reminded me of the friendships I had made before becoming a teen, before I worried about seeming vulnerable to others. No topic was off limits with Alberto. Nothing felt too earnest, or too cringey, or too honest. I admitted to missing my ex. He admitted to disliking Elton John. I admitted to emotional eating. He admitted to worrying about his health. I admitted to fearing death. He admitted to lacking fear of his own mortality. I admitted I struggled to please my sister. He admitted he wished he could visit his sister, in Italy, more. Until, eventually, I admitted I was lonely. And this man, who I had been encouraged to ring to help, to provide companionship to, admitted he wasn’t.

Loneliness is a difficult feeling to categorise and a horrible one to admit to. Perhaps, in the current context, loneliness has become less of a stigmatised emotion to voice. We have been forced to be alone. It has been out of our control. And so it can no longer be our fault that we have experienced it. I have been lonely. In truth, it was festering within me before the world slowed down. As a teenager, I had suffered from outrageous anxiety, which manifested as depersonalisation, a feeling of being distant and almost out-of-body. I was medicalised then, to help fit back in. In my 20s, I suffered with an eating disorder, as well as “medically unexplained” pain. And though my days were spent around people, in busy cafés, and my nights with friends, in truth, I spent most of my time writing in a notebook, dealing with characters inside my head.

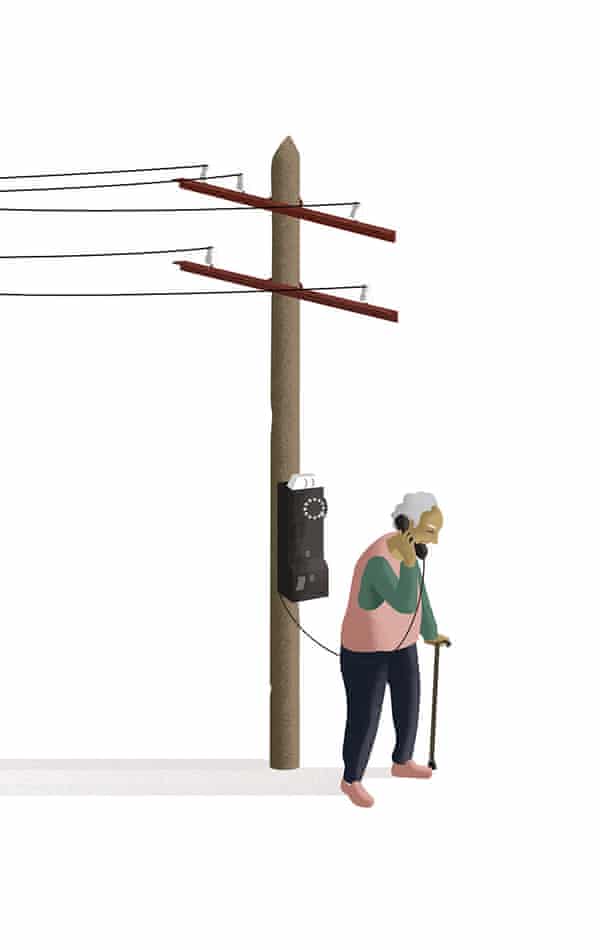

In April last year, analysis published by the Office for National Statistics found that 16- to 30-year-olds were twice as likely to experience loneliness as the over-70s. I described the feeling one day to Alberto.

“It’s a feeling of hunger,” I said.

“You feel hungry?” he said.

“No,” I said.

It is a metaphorical hunger, of course. A craving for connection. Social media hasn’t helped. And when you live in a city, with the mass presence of people all around you, that absence of connection is multiplied, to a point at which it can become unbearable.

On another call, I asked Alberto, “What about meeting someone? Do you think you might feel happier if you met someone?”

He replied, “I met many people, Daniella. I also met many people who were incredibly lonely who have been in relationships for far longer than you’ve been on Earth. The cure isn’t meeting someone, not really. And also, you said “happier” – happiness, we spend too much time searching for it. Sometimes it evades us. And that’s OK. We’re not meant to be happy all the time.”

One Sunday evening, while we were both cooking our separate dinners in our separate homes, I asked Alberto, “Why did you reach out to Mutual Aid if you weren’t lonely?”

“I was curious,” he said.

I searched further.

“How come you aren’t lonely, Alberto?”

He explained: “Three years ago I went to the Royal Albert Hall and to Covent Garden, a lot. Two years ago, a bit less. Last year, only once. As I’ve slowed down, I’ve learned to be with myself. I accept my life is changing, my body is changing. I live in solitude, but I’m not lonely, because I know myself.”

He told me that he had experienced a gradual transition into the “slow life”, whereas I had been thrown headfirst into it. He’d sat with himself for nine decades, experiencing loss, failure, joy, a lack of belonging, a broken heart and, over time and with patience, he had slowly befriended himself. So when the virus pushed us all indoors, nothing about being alone with himself surprised him. He’d been there before.

I continued to call Alberto as the spring turned to summer and we were briefly let outside again. I told him about tentative plans I’d made with friends, he told me about his walks around the park. He had remained vigilant, aware the virus hadn’t become any less deadly.

But then the autumn arrived, and when I called him he didn’t pick up. I tried again and again. Again and again no answer. Catastrophic thoughts flooded my brain. I contacted Mutual Aid, but they didn’t even know who Alberto was. By this point they had made the introduction six months before, and there had been many more “old man seeks friend” notifications since then. I thought of Alberto and called him daily. Nothing. I tried to get on with things. I emailed. I began to grieve. I called again. Nothing. I tried to accept fate, because that’s all I could do.

I rang once more.

“Hello?” he said.

Alberto had made a last-minute trip to Genoa to see his sister. He apologised, then asked how I’d been while he was away. I took a moment to reflect.

“I thought you were dead,” I said.

Alberto laughed. You can imagine the laugh, from the depths of his belly. It was contagious.

“And if I was,” he said, “you would have accepted it, too, and then you would have been OK. But for now, we can be in this together.”

In The Lonely City, the author Olivia Laing writes, “Loneliness is personal, and it is also political. Loneliness is collective.” Over the past year, our awareness of loneliness has gone global. And though loneliness remains terrible for some, even as our third lockdown is lifting, it feels now a topic more acceptable to discuss. I’ve discovered solidarity in the feeling. Alberto has taught me that we, all of us, are in this together, not just during a pandemic. And though we may not have been able to see each other face to face, or have the language or power to share accurately the feelings we have experienced, we can now at least hope to be honest.

When I rang Alberto one day to ask him if I could write about our friendship, I plucked up the courage to see if he might like to meet in person. We could grab a cappuccino at a local Italian café, I suggested. Face to face, still socially distanced. He took a moment to consider the offer. Then he said, “No, the phone calls are good enough,” kindly adding: “I haven’t had enough sun to show my face this year.”

My first response was abandonment – he was rejecting me. And then I sat with it, as I’d now learned to do. He enjoys being alone, I thought. That doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong. It isn’t a reflection on me, or our relationship. He is alone but not lonely. And so am I.

from Lifestyle | The Guardian https://ift.tt/3uaLXL2

via IFTTT

comment 0 Comment

more_vert