My sister’s illness was a mystery until the day before she died. In the spring of 2016, Fauzia was taken to hospital twice and each time she stayed in intensive care for days on end. Her doctors conducted tests, drew up hypotheses, disproved them, and called in more doctors until her medical team was engorged with expertise but no closer to a diagnosis.

‘The mystery remained even as we were told to gather around her bed in the ICU on 9 June 2016. After she had died, when my mother and I prised out the needles that the nurses hadn’t taken from her neck and wrist, she continued to bleed. My mother, a British Pakistani Muslim who practises her faith quietly but assiduously, whispered the Qur’anic surah Yaseen in her right ear and told me she had seen a tiny black pearl slip out from under Fauzia’s eyelid – a single jewel of a tear – which she had caught in the palm of her hand just before it disappeared, along with my sister’s soul. It was a sign, she said, a parting gift from her firstborn child, who was also the first to die.

I could see nothing of death in Fauzia as the bright red bubbles of life streamed out of her veins when we removed the needles. A horrible kind of magical thinking gripped my mind in the days that followed. I wondered if she was dead at all or if the doctors had misjudged this, too, assuming death when she was in a deep slumber, a modern gothic Sleeping Beauty.

Six months earlier, Fauzia had begun complaining of chest pains and heavy night sweats to her GP, but her X-rays had come back clear. Then her face swelled. She was taken to A&E and tested for jaundice and meningitis. Doctors said she had a blood infection they couldn’t yet identify. She discharged herself, growing impatient with their investigations, but was unable to breathe properly a few days later and was taken back to hospital. She was given steroids and appeared to get better, so they discharged her after 11 days. But the following month she was back in intensive care, for two weeks this time, weaker than ever with inflamed lungs, slurred speech and strange behaviour, which we were later told was due to brain swelling. She was so ill that doctors put her into an induced coma and carried out more investigations. Still no diagnosis.

And then she had a brain haemorrhage. It had started at around 5am on 9 June, the doctor told us when we rushed to the hospital later that morning. Some hours later, after a brain scan, they realised it had been catastrophic, but they still couldn’t name her illness. I wondered if it was a deadly new virus that lay on the outer reaches of medical science. We were told that in these circumstances, they could only declare someone dead after 24 hours. But there was no chance of recovery.

We were left dazed. Fauzia was not officially dead, but not alive either. However surreal it sounded, the semantic limbo gave me 24 hours of hope. If her illness had been so mysterious, her recovery could be, too. I turned to my mother, the believer in all unseen matter, and put it to her, but she looked small and silent, already sunken by grief.

The next day, Fauzia was moved from the open ward to a private area. A friendly nurse greeted me and told me to put on PPE. I had no idea she was in the room alone because she was being isolated. The nurse and I got chatting and I told him how they still didn’t know what was wrong with Fauzia. He looked at the medical notes and told me that there was a diagnosis.

“A diagnosis?” It seemed unbelievable that her elusive illness had been pinned down overnight, just as my sister had entered the holding cell between life and death.

“TB,” he said. “She died from tuberculosis.”

They had, I was later told, discovered it from retesting her spinal fluid from a lumbar puncture administered when she was still alive. They had not been looking for TB because they hadn’t thought of it as a possibility. But it had been there all along – “disseminating”, we were later told, from her lungs to other organs through her blood or lymphatic system.

Questions began to arise: when had they retested Fauzia’s spinal fluid – after her haemorrhage or before? Why hadn’t they thought of TB when they saw her lungs were inflamed? An infectious-diseases doctor had stood by her bedside and told me that TB, which I thought had been all but eradicated in the UK, had made a comeback in recent times – so why wasn’t it considered by the army of specialists? And was it just an awful coincidence that they had found a diagnosis the day before they switched off her ventilator?

Fauzia had had a difficult life. She had been dealing with depression and an eating disorder since she was a teenager. It had ravaged much of her life, and brought her into close contact with the harsh bureaucracies of the medical and psychiatric professions. She often spoke of feeling that the system was letting her down or failing to understand her. It was a system, she claimed, that seemed set on distrusting and disbelieving her because of her mental health. Now it turned out that she had been as unlucky in death as in life.

Until I was five years old, my parents shuttled back and forth between London and Lahore, trying to decide where to live. I was born in London but they returned to Pakistan in 1975, when I was three, hoping to resettle. But by 1977, money was becoming an issue in our paternal grandparents’ home, where we lived with our extended family. My father wasn’t earning anything while his brothers were all contributing to the running of the house. My sister and I were told abruptly that we were going back to England. I was appalled by the news.

Moving to London in December 1977 contained its own slow-burn trauma. We had been removed from the extended family and found ourselves thrust into poverty. The Technicolor life of Lahore was lost, and all turned black and white.

Fauzia was the only one of the three of us born in Pakistan and her early life was far less settled than mine. She didn’t meet our father until she was 13 months old because he was in London, trying to find a job before sending visas and air tickets for my mother and Fauzia to join him. They arrived in London on 23 October 1971. They landed at Heathrow to find that my father was late, so they waited in the arrivals lounge. My mother was dressed in a new shalwar kameez and Fauzia in a party frock. He arrived in a car he had borrowed from a friend, and when he saw Fauzia he reached out to hold her, but she, not knowing who he was, cried and clung to our mother. He asked our mother why she was crying and tried again, but Fauzia turned her face away. After that his mood changed and he spoke sternly to her in the car, telling her chup – be quiet – when she wouldn’t stop crying. Maybe he felt rejected in that first meeting, but it couldn’t and shouldn’t have set the tone for their entire relationship.

When I was born, my father couldn’t stop marvelling at me, I’m told. Perhaps he saw me as the firstborn because he was there for my birth. Rather than hiding his favouritism, he made it explicit. He told me, volubly, that I was adored and special. I was the daughter who could do little wrong. Fauzia was the problem child long before she had done anything wrong. Even the arrival of a brother two years later didn’t dismantle my primacy in my father’s eyes.

I grew up on stories of my father’s random cruelties towards Fauzia as a baby: of him making her mouth bleed by sticking his fingers into it and pulling at her cheeks, of shaking her and making her run alongside him, even when she grew breathless and tearful. My mother worried about leaving him alone with Fauzia. He would take any opportunity to tell her off, pull her hair, and say he couldn’t bear looking at her. Sometimes he refused to eat at the same table as her, so she would have to wait until he had finished. She would be blamed for the smallest misdemeanour and told that my misbehaviour or my brother’s was her doing because she was the eldest and had set a bad example.

There are no conflagratory set pieces of remembered violence from that time. My father just continued to treat Fauzia differently. I know now that his behaviour amounted to verbal and emotional abuse, but I couldn’t have named it as such then. Even now, it feels like I am betraying him, but it is correct to use that term. It still alarms me that family abuse can be so selective. The charges against Fauzia became normalised in our home. I suspect this is how some domestic abuse works: in pinpricks, pinches and a tsunami of micro-aggressions. It is what makes it so pernicious, and it is no less monstrous than scenes of bone-breaking violence.

My heart hardened a little towards my father following Fauzia’s death, but it is not as simple as that, either. I have seen him suffer, too. For the past 15 years he has lived with dementia. He is alone now, visited at his nursing home by no family members other than me. It’s as if he is paying penance.

His locked-in state makes any account of his actions unfair. I am painting pictures that he can’t challenge or correct. It would be easy to build an alternative narrative: that he was simply not as close to Fauzia as he was to me; that he was there to support her in adulthood; that he spent hours entertaining us as children. He loved us in different ways, he might say. Whatever the source of his complicated relationship with Fauzia, it is buried wordlessly inside him for ever.

When she was 16, Fauzia was moved upstairs to share a bedroom with me. This was when we started to become allies. We started discussing all the ways in which our parents had failed us: she spoke of our father’s unkindness towards her, and how differently he had treated me. She thought our mother had failed to protect her. I began to understand how different her childhood had been from mine. Fauzia also described her increasingly low moods, her sudden depressions.

She became my closest friend, a knowing, supportive older sister whose warmth I took for granted but whose pain I felt as my own. Despite her depression, she had bottomless optimism when I needed to feel more confident about myself in the world. “Of course you can do it, Arifa,” she’d say, in a sure voice, when I felt uncertain. “Why would you even question yourself?” We bonded over books, and her tastes shaped mine to create a language of intimacy between us: talking about a certain novel or artist became a way of defining ourselves to each other, and to ourselves.

Fauzia’s first major depression came in 1990, though none of us recognised it as such at the time. She had dropped out of her fine art foundation course, even though the course had meant everything to her. She was 19 and doing less and less, in a bathrobe most days and dragged down by paralysing lows. The depression seemed unknowable and monstrous.

My last meeting with Fauzia outside hospital was in May 2016. It was shortly after her first admission to A&E in April. There had been four years of silence between us. We had argued on and off for decades but this time, I had been the one to pick the fight. I can’t remember what triggered it but I felt all my old unaired resentments rising to the surface over the course of a meal and I rounded on Fauzia to tell her I hated her, shouting the words before storming out of the home.

Afterwards, my mother told me I needed to apologise, but I couldn’t because the anger, now out, was too big to put away and too irrational to explain. I was furious with her for her lifetime’s depression, for not being the sister she had once been, for making me feel like her oppressor when I had never betrayed her, and I felt it was she who had built up a narrative against me, calling me her bully when I had been her friend.

In the years of icy silence between us, I had missed her company, her careful listening, her passion for things, even if I had stayed angry. I felt a weight lift after we met at A&E in April, although a part of me remained apprehensive, because, however many fresh starts Fauzia and I had had, we always seemed to circle back to grudge-bearing and mutual resentment, either assigning ourselves our old identities or blaming each other for them.

Everything changed between Fauzia and me when I left for university. I remember how on the day I caught the train to Edinburgh she wouldn’t talk to me. When I asked her to see me off at the station, she refused to change out of her dressing-gown. She behaved as if I had wronged her. I thought she was being unreasonable, but I felt twinges of guilt all the same for leaving. A few minutes before the train moved out of the station, I saw Fauzia running along the platform with a scroll of paper in her hand. She got to me in time and I rolled the paper open to find her favourite painting – a still life of flowers in meticulous brush-strokes of oils in deep blues, purples and turquoises. It had been the only finished artwork she had taken to her art foundation admissions interview in 1989, and on its back she had written, “To Arifa – look – my first great work of art!! Fauzia”. I felt elated. We were still the best of friends.

Leaving home for university had meant leaving Fauzia when she was slowly falling apart. Did I abandon her? Was I, in fact, partly to blame for her depression? I felt these uneasy questions swarm wordlessly between us after I returned from Edinburgh. Maybe Fauzia planted them there. I suppose she had a right to do so: the legacy of having been my father’s favourite in childhood felt toxic when set against his brutal treatment of her. During my years away, Fauzia must have decided I had shown her cruelty, too, because she became snide and jeering when I returned.

It grew difficult to be with her, even in the times when we weren’t arguing, because everything came back to her bigger pain. Her suffering was insurmountable, it seemed, and I was fed up with being implicated.

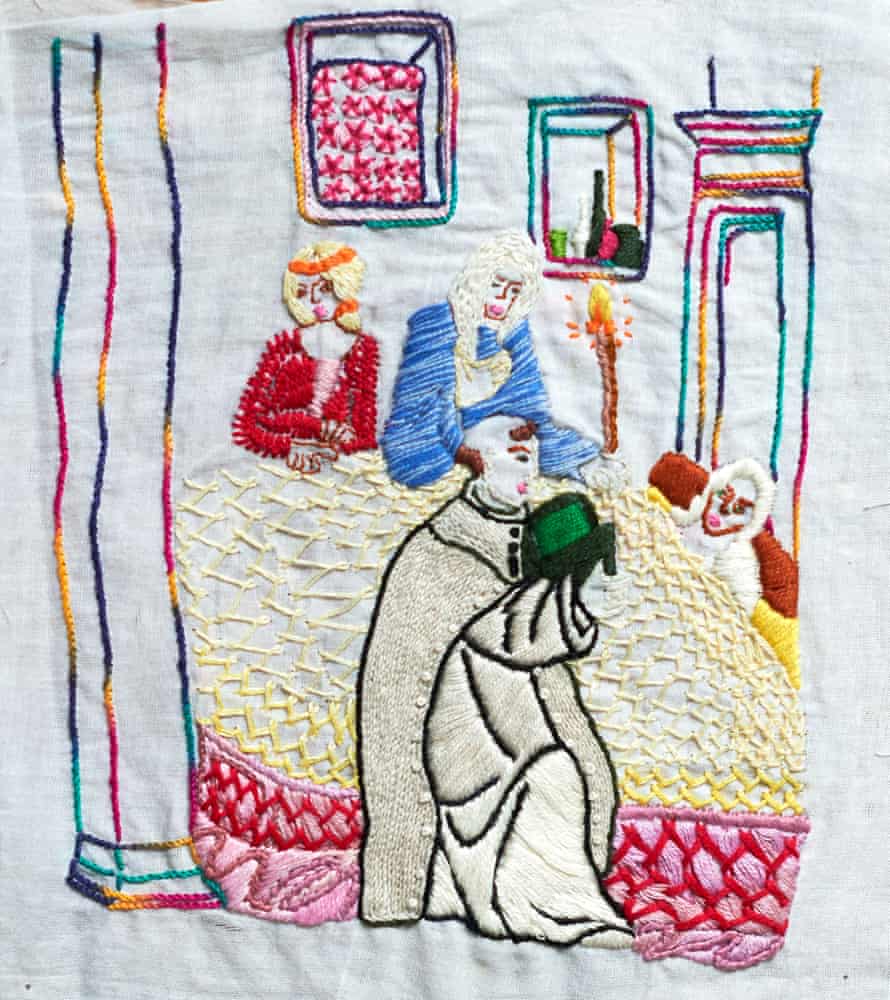

After being encouraged to go to a sewing class in her late 30s, she had returned to art school, at 43, and was midway through a fine art degree at Camberwell College of Arts, at which she was excelling, when she died.

When we gathered together her innumerable sketchbooks and portfolios a few weeks after her death, I began to look for clues to her inner world. I had been reluctant to look for fear of seeing things that would be painful to acknowledge. I knew I would find clarification of so much about Fauzia, but I would also see the ways I had misjudged her.

Looking at her art, I am surprised to find pictures of myself. In a sketchbook called “Artist’s Research” there is an image of me smiling and hugging our niece, one of our brother’s daughters. My eyes are open, my niece’s are squeezed shut with laughter. I recognise the image: it has been copied from a photograph taken in our mother’s home.

It becomes apparent that it is part of a project whose themes revolve around mythologies. There are seven more portraits of me, almost all in closeup, and most are on a double page, set against a classical painting featuring cherubim, biblical figures and saints drawn on the opposite side. I recognise each picture of myself from photographs that have been taken by the family. These images startle me for their likeness, but also the sense of being airbrushed in slight but significant ways. She has made my face more harmonious than it is – my nose is smaller, the gap in my top teeth is gone. I realise, with some apprehension, that it is deliberate. There is something sad about her intentional smoothing away of my imperfections, but the idealised tone of the words accompanying the portraits saddens me more: “She’s funny and honest!” is written under one.

I turn the page. Another smiling image of me with writing beneath it: “She is multifaceted, like all well-directed, hard-working human beings and her individuality is remarkable.” I look at my image and the saints on the opposite side of the sketchbook and it is clear I am being set beside the ideal. It goes on for several pages and the almost fantastical tone of the words is excruciating. I see in this the pain of being the “other” sister. Here is my elevated status in the family as the perfect daughter, and in its absence, the position she was given as my opposite.

There are two final images of me that bring a stop to the whole project. Here I am alone, in even more magnified closeup, and I am not idealised now. I look almost like myself, but small oddities have been inserted that make my face look gothic and ever so slightly grotesque: my features bent, my nose long and bony, my chin witch-like. Below the images, she has cut out a single printed word, in capital letters, from a magazine. I stare at it, surprised at first, then reminded of all the ways in which we distrusted each other: “DEMON”.

The word instantly casts the previous pictures in a new light. Here is what she was building to: my fall, from angel to devil. These last pictures remind me that, just as she was my demon sister for a time, destructive and dangerous in her anger, I was hers. It seems like a conclusion, somehow, but it was not the end of us, as sisters. I was not her demon sister at the end of her life, and she was not mine.

We were reunited, two months before she died. I had gone to her hospital bed with a racing heart, hoping to see her alive, showing her I was still there for her.

In the weeks and months after Fauzia’s death, we had to chase doctors repeatedly for a fuller explanation of why she had remained undiagnosed of an ancient infectious disease that might otherwise have been cured with a course of antibiotics.

Two months after she died, we were finally sent a summarised report of her case, which made it clear how hard the doctors had tried, but also that there had been “missed opportunities”. Her form of TB had been relatively rare and difficult to detect, we were told. As I began reading around the illness, I discovered that it was often elusive in character, and could also lie dormant in the body for decades before awakening and attacking the system, slowly and stealthily, from within. For all the gains of medical science, TB remains the unknowable, or at least not fully known, contagion.

I find myself thinking that we might have remained friends, had she lived. I wonder how she might have sketched me now, if I had sat for her myself. I hope I would not be the angel sister any more, or the demon, but wavering somewhere between, and that she would see me for the person I had become, with all the love and fear and flesh wounds of our sisterhood.

Arifa Akbar is the Guardian’s chief theatre critic. Her book, Consumed, is published on 10 June by Hodder & Stoughton at £16.99. To support the Guardian, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

She will be in conversation with Christina Patterson on Thursday 10 June at Blackwell’s online event; tickets available via consumed.eventbrite.co.uk

from Lifestyle | The Guardian https://ift.tt/2R8hT4s

via IFTTT

comment 0 Comment

more_vert