I arrived at La Europa, a Utah residential treatment center for at-risk teenage girls, at the age of 13.

The property, which used to be a bed-and-breakfast mainly serving newlyweds, had been converted three years prior. The pool had been drained, and had since gradually filled with dirt and rainwater. The tennis court was cracked, the fountain in the entryway had long been dry, and the pond in the backyard had more browned leaves in it than fish.

One thing remained the same: the room names, each named after a city in Europe. I moved into Brussels, and joked with the other girls about telling everyone back home that we’d spent the year traveling to Munich, Barcelona and Budapest.

Our treatment program was grounded in art therapy, so nearly every wall was covered in art. Because La Europa was short on money and often didn’t have canvas, most of the paintings were done on cardboard, little images of bananas or a brand logo showing through the paint if you looked in a certain light. Even our teachers were artists; the walls in the entryway were lined with portraits of girls who had completed the program that our art teacher, Jane, had lovingly drawn for them as graduation gifts.

Looking at them was like some kind of hope: yes, you were in a treatment center. Yes, you were likely going to be here for a year. Yes, it would be hard. But also: yes, you’d make it out of here, and like those girls on the wall, you’d be happy.

I spent the days before I was admitted with my parents in a house we rented in the mountains of Park City. We watched movies and my dad made me crepes that were fat like pancakes from the altitude. My mom wrote me a song, recorded it on GarageBand, and sheepishly handed it to me on a CD to listen to when I missed her.

Knowing I would be apart from them for months on end, we soaked up our time together as if we were a normal family on a regular vacation. All the struggles I’d been experiencing that led to our decision to admit me to La Europa were, just for a moment, not so loud.

Though only a few months prior, it was almost as if my parents hadn’t brought me to the emergency room after they found out I’d been cutting myself; as if I hadn’t explained to the doctor evaluating me that I wanted to die; as if I hadn’t overheard that doctor whisper “we think your daughter may be suffering from borderline personality disorder” to my parents in a hushed tone. I could pretend that night in the emergency room didn’t result in a weeklong stay as an inpatient at a psychiatric ward, pretend that the nearly six weeks I spent as an outpatient at the same ward were just a bad dream.

I didn’t need to replay the words “borderline personality disorder” in my mind, match my behaviors to the illness’ symptoms like a game I was a little too good at playing. I had the unclear sense of self, the pervasive feeling of emptiness, the extreme fear of being abandoned, the unstable relationships, the tumultuous emotions that shifted without warning. Borderline personality disorder isn’t typically diagnosed under the age of 18, but even with only a speculated diagnosis, I was a textbook case.

Yet for those few days in Park City, none of it seemed to matter.

When the time finally came for me to check in, my parents and I made the 45-minute drive to La Europa. As we pulled into the driveway, my mom turned around from the front seat.

“Don’t judge it on the first few days, Court. They follow you around for a while, but it’ll get better. You’ll love it.” Her voice was warm.

“I know.” I replied.

I didn’t, but it was too late to turn back.

After I had been strip-searched, had my belongings checked in, and said goodbye to my parents, I understood what my mom was talking about in the car. I was told that for the first week of my stay I’d be on what was called “safety”.

On safety you were required to be within 5ft of a staff – always “staff”, never “staff member” – at all times. You had to eat 100% of your food, wait 30 minutes to go to the bathroom after meals, and count out loud as you used the bathroom to ensure you weren’t throwing up your meal or trying to end your life.

A staff was required to watch you shower, you weren’t allowed to wear shoes, and when the girls who were on the levels above safety left for events off campus, you were required to stay. I was told that if after a week I hadn’t hurt myself or tried to run away, I’d be moved off safety to level one of the program. Then I’d be allowed to start showering alone, wearing shoes, and going off campus, though I’d still have to be in a staff’s line of sight at all times and count in the bathroom. Eventually, I’d work my way to level six, gaining privileges as I went, and then I’d be able to graduate and go home.

It took me a week to fully comprehend the new space I was in. It seemed everything at La Europa was peculiarly similar to the way it was everywhere else. There were friend groups and the worry of where to sit at meals. Girls played Mario Kart during free time and took guitar and dance lessons on Sundays. Summer school was a breeze, and on my first day in science class we made baked Alaska. In math class we watched episodes of Numbers and discussed the formulas they used to solve crimes.

Though we were all admitted because we were suffering from depression and trauma, and the myriad of ways they manifest, it seemed everyone was, for the most part, happy. There was a lot of smiling and laughter in a way you wouldn’t anticipate at a treatment center. Aside from the two hours a day we spent in group therapy, the three hours a week we spent in individual therapy, and our nightly “community” sessions where we spoke about our goals and what we were struggling with, we were almost normal teenagers. Like normality was within reach.

If I participated in a sort of intentional amnesia, I could almost forget about my near constant urge to self-harm; the weight of my depression and anxiety; the strange, empty feeling that engulfed me from the inside. I could pretend the week I had spent as an inpatient at a psychiatric ward, and the nearly six weeks of outpatient care that followed that stay, prior to attending La Europa hadn’t happened at all.

If I focused hard enough on playing Mario Kart or learning to play guitar, there would be no suspected diagnosis, no need for treatment, no sadness at all.

Becca showed up a week into what would become my 10-month stay. She looked down a lot and was shy in a way that was almost painful, with a voice she purposely made a few octaves higher so she sounded like a child.

When Becca moved into Brussels with my roommate, Crystal, and me, we were happy to have someone so sweet living with us. But our happiness quickly turned to frustration after we spent a few nights with her.

At night, whatever had brought Becca to La Europa came out with a vengeance. She kicked and screamed in her sleep, thrashing beneath her royal purple duvet cover. The night staff that monitored us every 15 minutes would wake her, and she’d have a few minutes of peace before succumbing to her night terrors again. Each morning, the staff would take her to the laundry room and she’d wash her sheets without any explanation.

For the first few days, Crystal and I didn’t understand, until our room began to reek of urine and a staff set up two fans to constantly try to air out the smell because the windows were permanently locked.

It was customary, when you arrived at La Europa, to share what brought you there during your first night’s community meeting. Becca refused to talk for her first three nights, but on the fourth night she spoke up.

She told us that she’d been raped daily by the men in her family since she was seven, and that when she was placed in foster care she began to be abused again. She bounced from foster home to foster home until she finally found a loving family that adopted her and sent her to La Europa to make sense of her experiences, and heal. No one knew what to say; I think Becca’s trauma was too deep for any of us to process.

We looked down and picked at our cuticles and thanked her for sharing, because it was all we could think to do. As soon as she spoke, I felt awful for having been upset about the smell that permeated our room. I was glad I hadn’t asked her why she was washing her sheets.

Everything at La Europa was routine: Wednesday was breakfast for lunch, Monday dessert night, Sunday night was pizza. We were allowed to shave on Wednesdays and Sundays, supervised by a staff, only with an electric razor, during “hygiene”, which was what we called getting ready, and it was scheduled into our day.

Every third Friday we went to the Salt Lake City Public Library, which had four stories and huge glass elevators that some girls, including me, were too afraid to ride. The other Fridays we spent volunteering at the soup kitchen or the animal shelter.

At every night’s community, we each, including staff, went around to talk about what we were working on in therapy, how we were feeling that day, and what our goals were going forward. On Wednesdays, the treatment team met all day to determine which of the girls who’d applied to level up would actually level up, who was up for graduation, and who was receiving a level drop.

On Friday nights, one girl would be allowed to choose where we’d go out to dinner, and her answer was always Chipotle. The staff knew all our names and orders by heart and to expect us at 6.30 sharp every Friday night. On Saturdays, we screened an approved movie, all gathering around to watch it on an old box TV.

Sunday mornings we’d wake up and deep-clean our house for three hours or as long as it took us, do homework, then have pizza for dinner, after which some girls would go to Alcoholics Anonymous while others of us had a two-hour period called “reflection”, where we were allowed only to journal or sit silently in our beds or read. Then we’d have hygiene, and go to sleep.

Usually at least one girl out of our group of 32 would have a breakdown each day, and at any given moment at La Europa you could almost guarantee that someone in the house was crying. Group therapy was usually hard; some girl would speak and unintentionally trigger another.

There were often days that marked a year since a girl had been raped, or had had to have an abortion; there were the one-month marks of sobriety for girls addicted to meth who yearned for it all the time.

But some days, there was a lull in the sadness in the house: every girl who applied to level up would have her request granted by the treatment team, no one would cry in group therapy, home passes would be approved. If the energy in the house was good, your therapist might be extra nice to you and take you to Stop & Shop to get you a candy bar or decaffeinated soda before your session, or let you have therapy in a park somewhere if it was sunny out.

During those days, I wondered if we were as broken as we seemed, or if we’d just had a lot of bad days that were strung together in a long row and we were finally out of the woods.

Other days, everything went wrong, and if one girl started crying, then everyone would start to cry with her. Sometimes we were ushered to our rooms quickly and without explanation, told that we were to stay in our beds and read or journal and be absolutely silent until further notice.

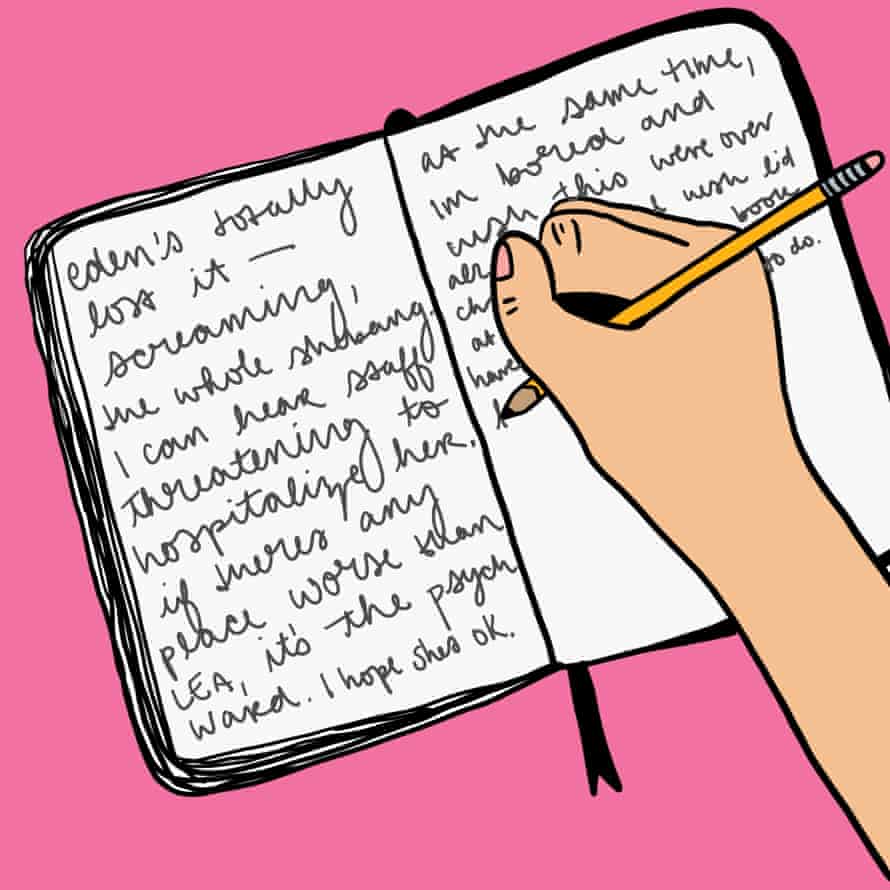

The first time this happened to me, I remember how Eden’s screams could be heard in every room of the house. Our great room had two-story ceilings, with a walkway halfway up that connected the second floor and overlooked both the great room and the kitchen. From the walkway, you could see Eden crumpled on one of the green suede couches below, her body heaving with sobs. Four staff surrounded her, ready to put her in a hold if necessary.

Until Eden’s situation was fixed, or she was taken to a hospital to be sedated, we all were to remain in our beds. None of us knew what had made Eden so upset, but we knew what had brought her here. We all had a story; Eden’s was that she’d taken a nail and hammered it into her leg down to the bone. The hole never healed and was always leaking, like a faucet that never fully shut off.

It seemed most of the staff had just as little information as we did. As we sat in our beds, fidgeting with both anxiety and boredom, they texted on their Nokia phones with impressive speed. I always wondered what they were saying, but on that day my curiosity felt urgent.

After two hours of mindless journaling and wishing I’d checked out another book from the library when we’d gone two weeks before, the staff watching us, Charlotte, stood up.

“We can have dinner now.”

And like that, it was over. Eden was escorted to her room by two staff. We didn’t know what she’d done then, but later we found out that a blade from her eyeliner sharpener had gone missing from the “sharps closet”, where the staff secured items they deemed dangerous. For the next 24 hours she’d sit in her bed on shutdown, the level of our program below even safety. Shutdown was La Europa hell.

As Eden went up to her room, the rest of us went downstairs for dinner. We gathered at our giant table and ate the horrible fried tofu our chef, Carissa, had made. We laughed and joked and told stories too loudly, happy to be able to talk again. Even though we were in treatment, even though we all suffered from depression and anxiety and so many of us had been raped and some of us had tried to kill ourselves and most of us cut ourselves when we were sad, we were happy. For that moment, at least, everyone was but Eden. And hopefully, one day, that happiness would last forever.

The girls at La Europa were always replacing one another; as one girl would graduate, another would be admitted. The girls I met when I first arrived were not the girls who were there when I left, and the personality of the house morphed depending on who was there at the time. That house was always changing, but it seemed to hold on to those who had been there before. The air in La Europa felt different from the air elsewhere, aged in a way. Like it knew something that we’d have to stay there to learn.

I often wonder what it would have been like to go to La Europa when it wasn’t a treatment center, but that period in the house’s history seems too painful to picture. I don’t want to imagine the fence in the backyard stripped of all its handprints, placed there by girls who had graduated but wanted to leave their mark on the place that healed them.

I don’t want to imagine a time when the house, and the world around it, was perceived as happier than it was when I was there, because I didn’t, and still don’t, believe there is a possibility of a place more beautiful.

Excerpted from The Way She Feels: My Life on the Borderline in Pictures and Pieces by Courtney Cook. Published with permission from Tin House.

from Lifestyle | The Guardian https://ift.tt/3tSp8KY

via IFTTT

comment 0 Comment

more_vert