Do you know your urethra from your clitoris? And could you locate either of them on a diagram? According to a survey of patients in hospital waiting rooms, half of Britons could not identify the urethra, while 37% mislabelled the clitoris – regardless of their gender. Meanwhile, just 46% correctly identified that women have three “holes” down below.

Dina El-Hamamsy, a senior obstetrics and gynaecology registrar, now at Addenbrookes hospital in Cambridge, and her colleagues, conducted the survey out of concern that many of their female patients were confused by the nature of their medical problems.

“A lot of women don’t understand the difference between urinary incontinence and a prolapse. Also, when they put complaints in, there’s a lot of confusion about what their condition was, and how it should be addressed,” El-Hamamsy said.

The team distributed anonymous questionnaires to 171 women and 20 men attending general outpatient or urogynaecology clinics at a Manchester teaching hospital. They were asked how many holes women have down below (in their private parts), and to name them. Fewer than half identified the correct number.

Co-author Fiona Reid, a consultant urogynaecologist at St Mary’s hospital, Manchester, said: “We do see women who don’t understand that there is the urethra, the vagina and the anus. They seem to think that the urethra and the vagina are the same thing.”

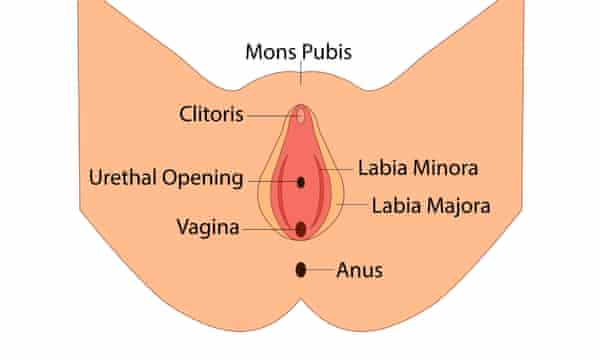

Participants were also given a diagram of the area, and asked to label as many structures as they could, using their own words.

Of those who attempted the labelling – and almost half left this section blank – just 9% labelled all seven structures correctly. Most people correctly identified the vagina and anus, while only 49% labelled the labia, and 18% correctly identified the perineum – the area between the vagina and anus. There was also confusion between the clitoris and the urethra.

Women were more likely to label the vagina and anus correctly than men, but there was no difference for the other structures. White ethnicity and higher levels of education were also associated with greater anatomical knowledge. The study was published in International Urogynecology Journal.

“It’s horrifying that people know so little about the vulva and female anatomy,” said Lynn Enright, the author of Vagina: A Re-education. “It’s not that surprising though. I think we are much more familiar with diagrams depicting the female reproductive system – the uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries – than images of the external genitalia, correctly labelled.”

The team also assessed people’s contrasting knowledge about general and female-specific medical conditions. Whereas most people understood what stroke and diabetes were, 53% had an understanding of what a pelvic organ prolapse, while only 23% knew what fibroids were – even though both conditions affect a third of women at some point in their lives. A prolapse is when one or more of the organs in the pelvis slip down from their usual position and bulge into the vagina. Fibroids are non-cancerous growths that develop in or around the uterus, and can cause heavy, painful periods and general discomfort.

Reid said: “I think we need far more women’s health education from a young age. In schools we need to be talking about issues to do with female genital anatomy, and people need to know about their health. They need to know about the importance of pelvic floor exercises and things like that because otherwise the first time they hear anything about it is probably when they’re pregnant with their first child, and at that point there are far more things on their mind.”

The study also raises questions about women’s ability to consent to medical procedures. Stephanie Shoop-Worrall, an epidemiologist at the University of Manchester, who was also involved in the research, said: “If a doctor is going to examine you, or suggest any kind of treatment plan, you need to fully understand what’s going to happen, and the risks and benefits, to be able to give permission. If people are coming in for their hospital appointment and not understanding basic anatomy, or what’s even wrong with them, how can they properly consent to treatment?”

Enright said: “You have to wonder: what are the long-term implications of people being so ignorant of their own bodies? What does that mean for people’s sex lives? What about the conversations they have with their GP when they encounter an issue? We know that too often pain is just accepted as a normal part of being a girl or woman or having periods – it’s worth thinking about how not having the words to describe pain or where pain is occurring could affect that.”

from Lifestyle | The Guardian https://ift.tt/2SKudIE

via IFTTT

comment 0 Comment

more_vert