We haven’t just been doomscrolling, homeschooling and working through our screens these past 12 months. We have also been shopping.

Online shopping has rocketed: UK sales were up 61.4% in December compared with the same time last year, according to the Office for National Statistics. Last month, when Asos and Boohoo bought high street stalwarts Debenhams and Topshop, and turned them into online-only brands, this pandemic-driven trend took on an air of permanence.

If the shift towards online shopping remains, it will have a profound effect on the way we live. It may close the chapter on shopping as a leisure pursuit, a major part of female history since the turn of the century, when trips to department stores gave women rare freedom from the house. It could also impact the way we dress. Retailers design differently for online, pushing styles that are more likely to fit a range of bodies, and less likely to be returned, majoring on elasticated waistbands and roomy frocks (the Zara spotty dress of summer 2019 was the ultimate e-shopping piece).

But the online shopping boom could also be terrible for the environment, from the rise of delivery trucks, to a mountain of returns. Here’s how to avoid contributing to that, finding clothes you love even when you can’t feel the fabric against your skin.

Get a tape measure

Working out whether a 2D picture on a screen will fit your 3D body is one of the biggest challenges. Shopping with brands you know, and love, can help, but isn’t foolproof.

A lot of big retailers give extensive size information. A typical listing for an M&S top, for example, includes a guide to seven categories of fit, with diagrams demonstrating how each is designed to hang, as well as advice on how to measure your body. Reviews can be useful, too, with listings on sites such as Hush featuring hundreds of customer views on whether an item runs big or small, and whether they had to return it.

Other big brands increasingly feature data-driven tools that ask customers for their height, weight, age and bra size, and then recommend a size based on data from previous customers’ purchases. The days when avatars will be trying on clothes for us don’t feel far off, with Browns Fashion already using augmented reality to allow customers to virtually “try on” trainers and watches, and Amazon developing virtual fitting rooms.

Small brands may not compete on tech, but some make sizing conversations part of a reassuringly human service. Yvonne Telford, founder of Kemi Telford, which specialises in highly pattered dresses and skirts, makes a point of asking clients to take their measurements before they order and giving customers personal guidance. Lots of small, online-only brands offer tailored pieces, too: at By Megan Crosby, prices run from £50 to £250.

Many eBay and Depop sellers give granular details about an item’s measurements including, for example, waist, thigh, inside leg, ankle and rise for a pair of trousers. This can be very useful if you take a garment that fits you brilliantly from your wardrobe, lie it flat and compare it.

Even when you’re confident you have the closest possible size, you do not truly know how the item will sit on your body. A lot of brands detail the height of the model, allowing you to do a sort of conversion. “When I’m looking at a dress on a model,” says my colleague Jess Cartner-Morley, “I think about the hemline completely differently – a knee-length hemline could be a midi.”

Sometimes regular sizes will never be right; then, alterations are your friend. Model Lauren Nicole Coppin Campbell regularly gives her garments tweakments at her local launderette. “Sometimes brands assume that plus-size women are very tall, and I’m not, so I have to get a lot taken up, or nipped in at the waist. It can be annoying, but I’d rather have pieces that I love and can continue to wear,” she says. She also gives kudos to Kai Collective and the Never Fully Dressed Instagram feed, which show the same items on different body shapes.

Edit

Set your parameters tightly. “I do everything I can to avoid scrolling through pages of clothes. Taste fatigue sets in quickly,” says Cartner-Morley. “I edit it down to brands I like, bring the maximum price right down, set my size, do everything I can to narrow it down.”

“Stuff overload” can feel even more overwhelming when buying secondhand, with sites such as eBay, Depop and Vestiaire Collective offering an incredible array. (Also, many private sellers on these sites don’t accept returns.)

Thrifter extraordinaire Bay Garnett, who has dressed Kate Moss in vintage for Vogue, recommends specificity. She will spot a designer look she loves and recreate it; she recently had a catwalk-inspired urge for “a men’s shirt, preppy book editor 1970s – ” look and bought two on Oxfam – one by Yves Saint Laurent, one by Pierre Cardin – for under £20.

Minimise returns

Much of my youth was misspent in the changing rooms of Big Topshop (RIP) trying on different garments, and identities, but not necessarily buying any of them. Until a few years ago, I applied something of that approach when online shopping, too, deciding what I would keep only after I had seen the items on my own body. I didn’t realise I was complicit in a huge problem.

With online shopping, says Dilys Williams, director of the Centre for Sustainable Fashion, “we’re pressing a button to send someone to go around a warehouse, find several garments, wrap each of them separately, send them out. Then, if we’re sending most of them back, that means an extra van or bike.” Worryingly, a lot of returned garments will not be resold. Many retailers do not have the technology to handle large volumes of returned goods, and a good deal of returns arrive damaged, or after the item has come off sale. A 2019 US report suggested that around 25% of returns are thrown away by retailers, and much of the further 75% is rerouted at a loss, either to consignment sites, or shipped abroad.

One tantalising vision for the future is offered by Harper Concierge, which will deliver a selection of pieces and sizes, for customers to try in their house, while a courier waits (the service is only in London for now, and used by a handful of small, largely high-end brands, including Me+Em, Shrimps and Amanda Wakeley). Otherwise, opting for companies that use less damaging delivery methods (electric vehicles, bikes) or walking to your nearest click and collect may be greener. But buying fewer items, carefully, is an obvious way out.

Williams describes the worst of online shopping as “a manifestation of what it looks like when new technology is applied in a way that doesn’t count the value of things. We are sucked in by the amazing images online, by a transaction that seems low-risk, cheap, just a click. But are we getting clothes we really love? Or buying things we have to return, or let languish in our wardrobes?”

The answer, of course, is to be as considered as possible about any purchase. Writer and former fashion editor Carolyn Asome maintains a “ruthlessly edited wardrobe and a mental checklist of what is missing, what could be updated, what needs to be repaired”. Buy clothes only if it fills a gap in your long-term list; also, give yourself a self-imposed cooling-off period and see if you still want it.

Georgina Wilson-Powell, founder and editor of Pebble magazine and author of Is It Really Green? recommends adhering to the 30 wears rule: “To work off the clothes’ carbon emissions created during production, you need to wear it 30 times. If you don’t think you’ll get that out of it, don’t buy it,” she says.

Work out what suits you

There is an advantage to shopping from home. It is here that the secrets of your personal style will reveal themselves, in the garments you wear on repeat and feel great in.

“Look at your favourite clothes,” says the Guardian and Observer’s menswear editor, Helen Seamons. “Where is the waistline, what’s the neckline like? Chances are they are all similar, so that’s what ‘suits’ you. Same with fabrics. If everything you love is jersey, then maybe silk isn’t going to work.”

Stylist magazine’s fashion features editor Billie Bhatia knows what works for her. “Fabrics such as jersey, satin and silks cut on the bias, and knits can have more natural give than, say, a linen or a denim. It’s also worth zooming in on waistbands to see what the closure is – side zip, poppers, elasticated – as this can impact sizing, too.”

Support small ethical brands you might not have access to IRL

Accessibility is one of the upsides to online shopping. Smaller brands are usually happy to talk to customers over email, too. “They love helping customers find something they’re going to love: you’re not just a sale,” says Wilson-Powell. Many also offer lifetime guarantees, repairs, and upcycling services. Mud jeans are one of her favourites: “You can even lease them, paying monthly and get a new pair each year, while your old pair is recycled.”

The Good On You website has ideas for ethical brands to try and looks at well-known brands’ ethical credentials. Ethical Superstore, Gather & See and Wearth London have curated selections of brands to choose from. Trouva aggregates products from the kind of stylish local boutiques you might want to support during the pandemic.

There’s a real community of small fashion businesses on Instagram, says Holly Watkins, founder of super-chic secondhand emporium One Scoop Store. “It levels the playing field for what’s available to you,” she says. Watkins, who has 24,900 followers, has connected with Virtual Vintage Market and makers’ markets on the app during the pandemic.

Vintage and handmade items are also Etsy’s USP, although plenty of mass-produced items pop up in listings. To check that the piece you’ve found is handmade, and unique, try looking through a range of Etsy listings, and searching on Google Shopping for the same key words. Look out for sellers with negative reviews, or gigantic inventories, which should ring alarm bells.

Know your fabrics

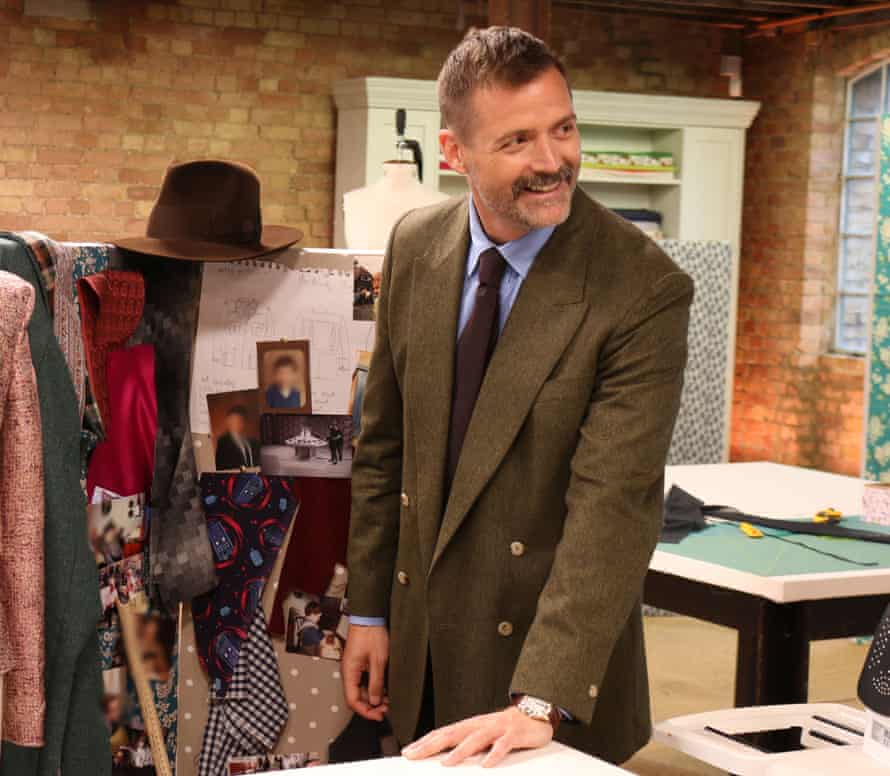

While not being able to feel the weight or see the drape of a garment is a disadvantage, most websites do give full details of fabric composition. Designer and Great British Sewing Bee judge Patrick Grant advises aiming for 100% natural fibres, notably cotton and merino wool, wherever possible. Though there are exceptions (sportswear and some outerwear, for example), for the most part, he says, “synthetics are only used to lower the cost of making a product”.

At Grant’s ethical label, Community Clothing, “we try to tell you as much as possible not just about the type of fabric but the weight – for example, a pure cotton loopback jersey weighs 400g.” That might be twice as much cotton as a fast-fashion equivalent, and should last a lot longer. There should be specifics listed for fabrics that claim to be sustainable, such as the GOTS standard for organic cotton.

Zoom in on the photographs, to try to get a better idea of fabric quality, says Seamons. She recommends looking at a few different listings of the same item. “I will look on all the websites that sell it, as they often light things differently.”

The online shopping process has been designed to be so seamless that you can fill up a basket without even noticing. In fact, the opposite should be true: when you can’t do a twirl in the fitting room, you need to do your homework. After all, who wants to send drivers out needlessly or spend a day in a post office queue?

from Lifestyle | The Guardian https://ift.tt/3vig8AN

via IFTTT

comment 0 Comment

more_vert