Capturing the attention of the discerning late millennial and Gen Z crowd is a marketer’s dream. It’s a dream that Depop – a platform for buying and selling secondhand and homemade clothes – is fast realising.

The UK-based virtual fleamarket launched in Australia just over a year ago, and now estimates around one quarter of Australians between the ages of 15 and 29 have signed up. That’s more than 1 million young people drawn to their message of environmentally-friendly fashion, wrapped in an achingly cool influencer aesthetic.

CEO Maria Raga has proclaimed Depop’s mission is to disrupt fashion the same way “Spotify did with music, or Airbnb did with travel accommodation”.

Depop is taking on the polluting practices of fast fashion by promoting circular consumption, and on 29 January 2021, committed to becoming fully carbon neutral by the end of the year. In a statement, Raga said “creating a better future for fashion and ourselves is a shared goal, not just for Depop, but for everyone. Our plan is the first step towards that future, and Depop becoming the world’s most diverse and progressive home of fashion.”

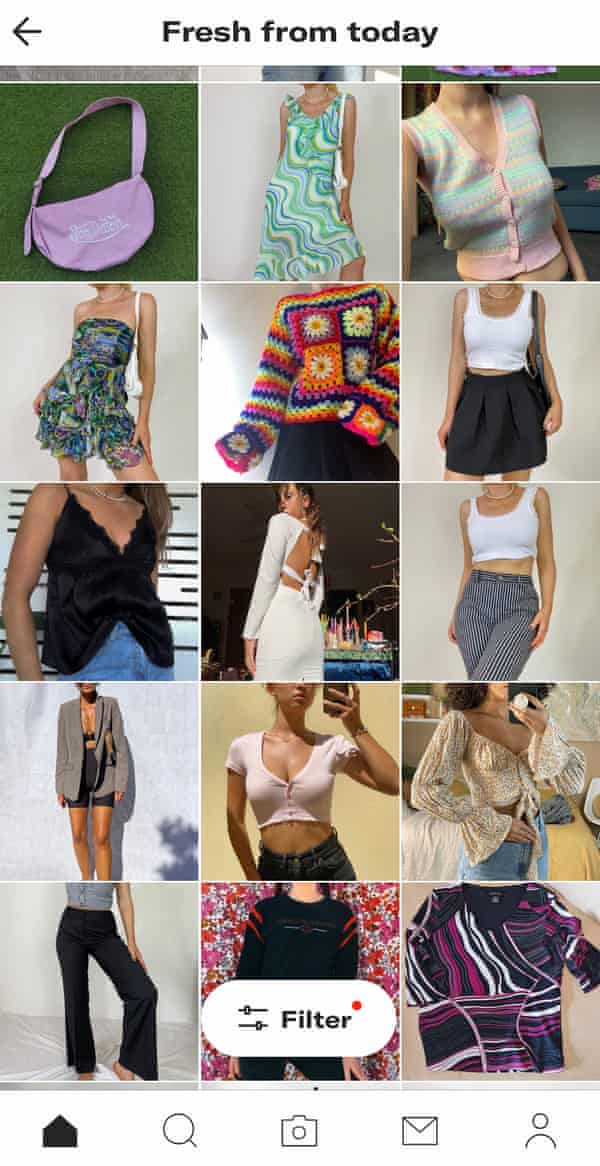

Depop’s popularity isn’t just down to its sustainability pitch, though. The app looks very similar to Instagram, allowing users to build a visual profile and gain a following, a “social shopping” model that blurs the line between buyer and seller (60% of users do both) and makes it particularly compelling to browse through.

But as large social platforms face questions about the communities they facilitate, Depop has not escaped the baggage of the model it draws from. For many users, the experience of browsing Depop does not feel as diverse as the platform’s stated ambitions.

“I think it’s an amazing service,” Jasmine, a 19-year-old user from Brisbane says, “but this comes at a price. It’s like the bad stuff of Instagram, but on Depop.”

Jasmine finds herself endlessly scrolling through Depop’s Explore page – a curated list of items for sale, where she obsesses not over the clothes, but who is wearing them: “slender, white, female models.”

Jasmine, who has body dysmorphic disorder, is not alone. “As much as I love Depop it triggers me personally in a few ways, as someone struggling with an eating disorder,” says Imogen, an 18-year-old New South Wales seller, who says she has fallen into unhealthy patterns of behaviour, specifically after spending time on the app.

On subreddits and Facebook groups, sellers confess that their relationship with Depop is affecting their wellbeing and body image, writing posts like “Does anyone else feel like their body isn’t good enough for depop?” and “My body will never have that ‘depop aesthetic’”. Last year, a petition started by a coalition of US-based sellers claimed Depop “is not an inclusive or supportive place for plus-sized sellers.” Other users complain on Twitter, with varying degrees of seriousness, that their relationship to the app is “toxic”.

Many complaints involve direct instances of rudeness and harassment, such as leery comments and direct messages – a well-documented issue (there’s even an Instagram account dedicated to odd interactions, @depopdrama with over half a million followers).

Depop says it is active in moderating this behaviour. “We have an absolute, zero-tolerance approach for any predatory or abusive behaviour of any kind … Our dedicated Trust and Safety team proactively monitors for abusive and predatory behaviour using machine-learning scripts to detect this quicker and more efficiently,” Depop’s Australian general manager, Aria Wigneswaran, says.

But in the case of users like Jasmine, the problem isn’t bad apple users, but how buying and selling makes them feel. And that, says Wigneswaran, is “a really tricky issue … and we want to make sure we resolve it”.

Depop told Guardian Australia it actively promoted body, racial and ethnic diversity. On the Explore page, which is manually rather than algorithmically curated, a quota aims for 30% diversity. It encourages users to report harassment in-app and says it aims to respond to 95% of reports within three hours.

But a user’s inner experience is a lot tougher to detect. “You can’t predict how people will interpret [an image]” says Natalie Hendry, a researcher in social media and youth mental health at RMIT, “but if enough people feel this way it doesn’t matter what Depop have programmed.”

Hendry says that Depop users’ struggles are societal problems, which are amplified when you add commerce into the mix. “Disordered eating and body image issues arise wherever visibility is a requirement to be successful,” she says.

According to Depop’s sellers’ guide, “model photos” – pictures that feature someone wearing the clothes – are 60% more likely to sell clothes. This sets Depop apart from apps like Etsy or eBay, where it is more likely clothes will be displayed on a coat hanger, mannequin or flat on the floor – rather than on the body of the seller, or a model they’ve hired. “That’s the stat and that’s the reality,” Wigneswaran says of the seller guidelines. “But it doesn’t mean you need to do that,” she explains, adding that many of the platform’s top sellers present their stores without modelling their clothes.

The rewards of becoming a successful Depop seller are high. Stories of Depop millionaires, and a shortcut to influencer fame, are a particularly alluring prospect for the first generation in 30 years to come of age in a recession.

Mikhaila Simpson, 23, and Ursula Cash, 27, run a butch/femme plus-sized Depop store, @xanthesdad, which they began after losing work at the start of the pandemic. They are exactly the kind of body-diverse users Depop are hoping to attract. The pair say that for the most part their experiences have been empowering, and financially successful.

But, there have been downsides. “The way it’s designed … is just not benefiting creators who are really trying so hard to be seen,” says Simpson, who feels her visibility on the app is more limited, as a larger-sized seller. “We’ve had comments towards our bodies,” adds Cash. “We just have to remove it, move along and not give any space or time to it.”

“It’s tough for a platform to be responsible when it also goes against their operating aim: to enable people to sell clothes and take a cut of that money,” says Hendry. “Can a problem that is bigger than the market be solved by the market?”

Jenny L Davis, lecturer in sociology at the Australian National University, is skeptical. She says that while technology cannot make people do things, it can “rewards those who adhere to community values.” If “the community values derive from a culture that prefers thin bodies … Given this reward structure it makes sense that young women on the platform feel a pressure to conform.”

“In the case of Depop … the app’s designers may not have intended for this outcome,” Davis says. “What’s more likely is that they designed … for profit maximisation, not considering the … impacts of those whose bodies would be on display.”

Users like Jasmine, Imogen, Simpson and Cash always have the option of swapping to a less body-focused clothing resale app. But in this, sense Depop is a victim of its own success. Despite their issues, they all enjoy the creativity of styling a shop, and are committed to ethical fashion consumption. Depop feels like the best platform to fulfil those needs.

“These are big challenges,” Hendry says, “they’re not going to be dismantled if Depop disappears off the planet.”

Adapting to a digital landscape, becoming more sustainable, and authentically embracing diversity are three of the biggest challenges facing the fashion industry in 2021. Depop is out in front of the first two, but despite its own stated wishes, the final hurdle may prove the most difficult.

from Lifestyle | The Guardian https://ift.tt/3rLighS

via IFTTT

comment 0 Comment

more_vert